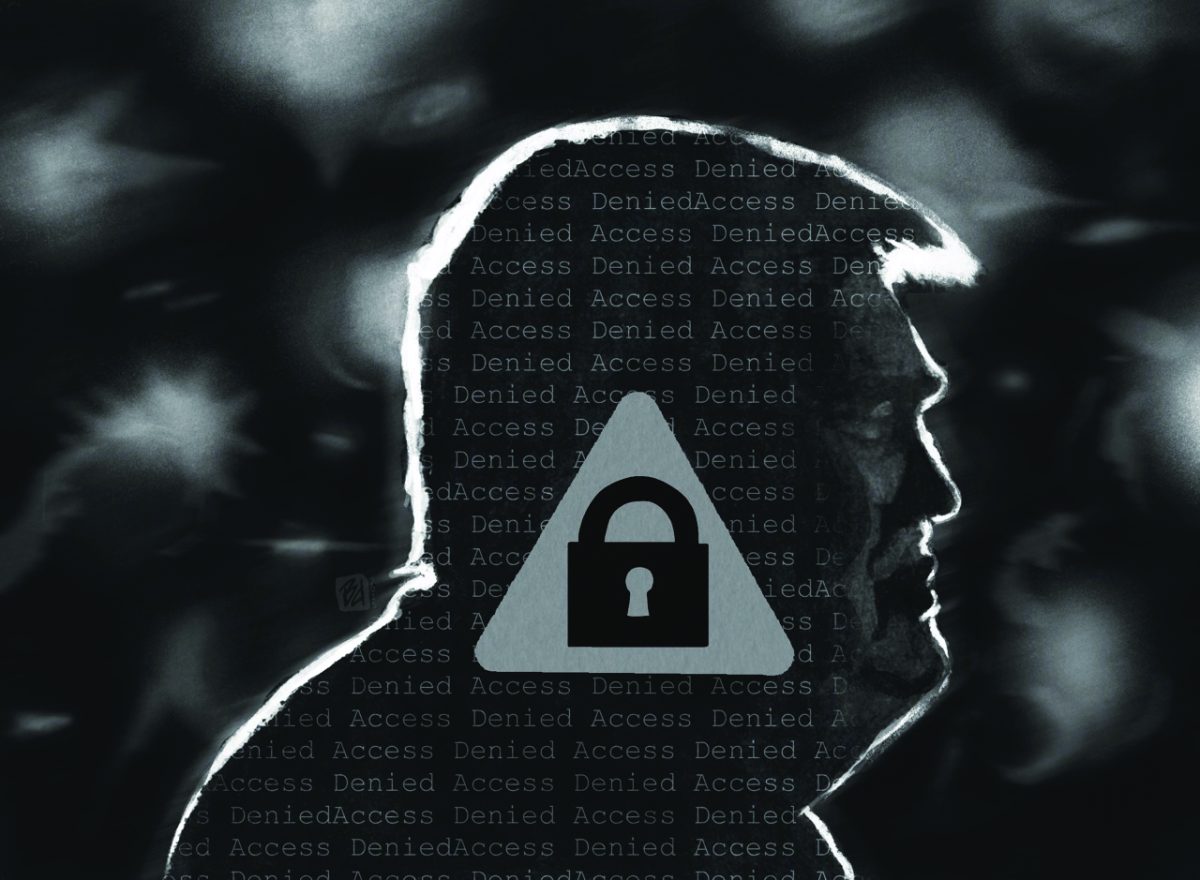

The role of journalists in a free society is to provide a check on power – to make sure that all the decisions governments and electorates make are informed by the whole truth.

To be able to do this, journalists cannot be coddled in their education. They must be trained from the very beginning to go tough on people who would conceal and mislead. The very possibility of censorship keeps them on a leash.

“What I’m hearing at the college level is that students are arriving in a damaged state,” Frank LoMonte, executive director of the Student Press Law Center, said, according to the Poynter Institute for Media Studies.

“They have been trained to believe that publishing material that upsets people is a bad thing. They have been trained if you ask too many tough and embarrassing questions of your institution that your story can be killed and you might personally be punished,” he said.

The Brookhaven Courier has long been supported by campus staff, faculty and administrators, as well as by the Dallas County Community College District as a whole. The publication has maintained its editorial independence and has not faced any real threats of censorship.

But other student publications around the country have not been so lucky, and The Courier’s luck could run out one day, too – unless New Voices legislation applying to colleges is passed in Texas.

The story of student press rights began 50 years ago when they were solidified in a historic U.S. Supreme Court decision, Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District.

That 1969 decision stated that school administrators could only censor student speech if it “materially and substantially interfere[d] … in the operation of the school.”

But those rights came under attack in the 1988 Hazelwood v. Kuhlmeier ruling, which argued that schools can censor speech in school-sponsored publications if the censorship serves a “legitimate pedagogical purpose.” It went on to provide examples of what can be censored: pieces of speech that are “ungrammatical, poorly written, inadequately researched, biased or prejudiced, vulgar or profane, or unsuitable for immature audiences” can all qualify.

It did not define any of those criteria, so they remain highly subjective and open to interpretation, giving school administrators relatively broad powers of censorship over student publications.

While both rulings were originally meant to apply only to primary and secondary schools, colleges have begun to see their effects, too. For example, the 7th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals ruled in 2005 that Hazelwood was the “starting point” for college media censorship cases in its jurisdiction.

“New Voices is a nonpartisan, student-powered, grassroots movement that seeks to protect student press rights using state laws,” according to the SPLC. As of 2019, 14 states have passed New Voices laws.

Texas’ New Voices laws, Senate Bill 514 and its equivalent, House Bill 2244, are currently working their way through the Texas state legislature. If passed, they would restore speech protections in K-12 public schools to Tinker levels.

The fight for student press freedoms starts from the bottom up, and it hinges on the passage of SB 514 and HB 2244.

Leah Waters, the state director for the Texas Association of Journalism Educators, testified in front of the House Public Education committee and the Texas Senate Education committee in Austin in support of both bills.

“The real enemy to scholastic press rights – for both scholastic journalists and administrators – is Hazelwood,” Waters said. As a journalism adviser at Frisco Heritage High School, she said this became apparent to her last year ahead of her students’ coverage of a walkout in support of “common sense gun laws.”

The Frisco Independent School District stepped in days before the walkout, notifying Waters that her students would be prohibited from covering the event.

Waters contacted the SPLC, notified them of the situation and gave their statement to the principal, who passed it along to the district administration.

The statement read, in part: “You may want to remind your administrators that attempting to censor this coverage will only draw attention to themselves and paint them in a fairly poor light. We’ve all seen the power of these young voices as they lead our nation in this important dialogue, and I believe your administration is aware that these voices will not be easily silenced.”

The district relented, and Waters’ students covered the walkout. But only two of the nine high school publications in Frisco ISD reported on it. Regardless of its intentions, the district acted against the rights of the nine schools’ student media outlets.

In their current state, the two pieces of legislation apply only to K-12 public schools. This approach seemed to be the most feasible way to get the laws passed, Waters said. Once passed, she said, the laws could be amended to include private schools and two- and four-year colleges, as well as private universities all over the state.

And they should be.

The possibility of censorship robs student journalists of the experience they need to cover the “real world,” sending them into the field with the idea that some truths are too ugly to be told. We must not allow that to become the case in Texas.

In these times, when the world is more susceptible to so-called “fake news” than ever, it is of the utmost importance the journalists of tomorrow are learning to report reality.

Categories:

Students need freedom of the press

May 6, 2019