By Jacob Vaughn

Managing Editor/Music Editor

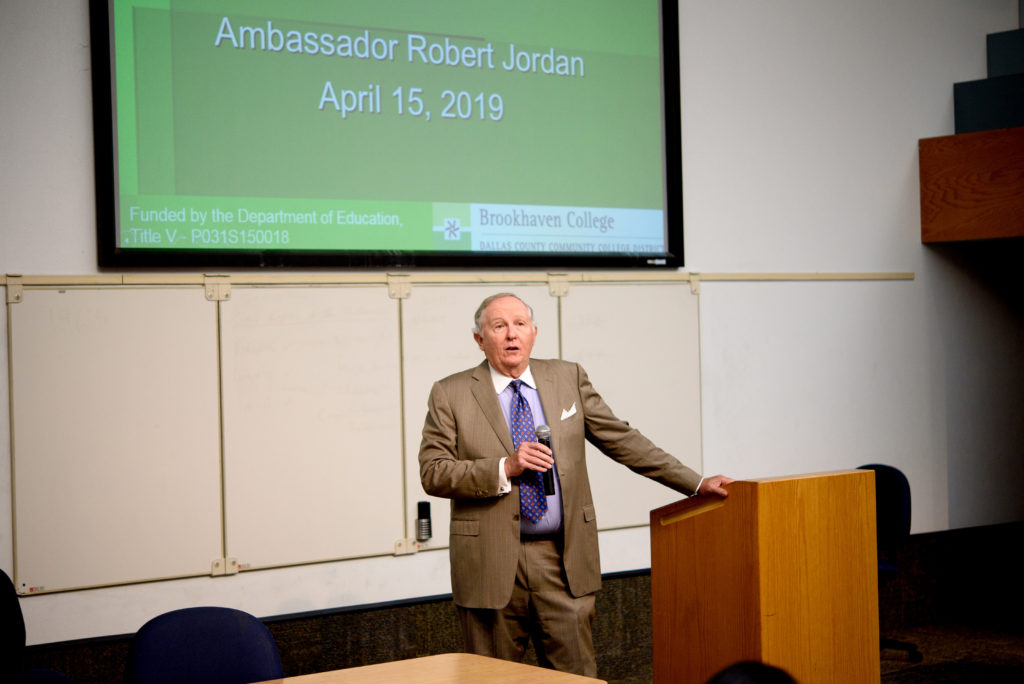

Jamal Khashoggi, a columnist for The Washington Post, entered the Saudi Consulate in Istanbul Oct. 2. Surveillance video shows Khashoggi entering the consulate, and seemingly leaving sometime later. However, he did not make it out alive, Robert Jordan, former U.S. ambassador to Saudi Arabia, said during a discussion on Saudi free speech and media April 15 in Room K234 at Brookhaven College.

Today, Saudi Arabia has laws on the books defining terrorism as anything critical of the royal family, the king or the government, Jordan said. “Even the mildest kind of dissent could be punishable by imprisonment, lashes or even death,” he said.

He said current Saudi crown prince Mohammed bin Salman Al Saud is now suspected to be responsible for more press atrocities, more repression of dissent and more thuggish behavior toward journalists and those who seek freedom than any other government leader on Earth.

CONFIRMATION

Jordan’s formal nomination for the position was to take place Sept. 7, 2001. “But they lost the paperwork,” he said. The nomination was rescheduled for four days later. However, it did not happen then either.

That day, Sept. 11, 2001, 19 members of al Qaeda hijacked four U.S. passenger airliners and committed the deadliest act of terrorism on American soil in U.S. history. The nomination finally went through Sept. 12, and his confirmation hearing in front of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee was held less than a month later.

During Jordan’s time as ambassador from 2001 to 2003, he met a number of Saudi journalists. They were a dedicated, respectable, hard-working bunch of people, he said. While the same kind of formal legislation was not in place to act against them as there is now, these journalists would often practice what Jordan called self-censorship. “They would be very careful to not print something that will be offensive to the royal family, or at least to the senior leadership,” he said.

MEETING KHASHOGGI

Jordan read three Saudi Arabian publications printed in English while ambassador: Arab News, Saudi Gazette and Al Watan. Khashoggi worked at all three at one time or another. Jordan met Khashoggi during the first of the journalist’s two stints as the editor of Al Watan in 2003.

“Jamal was a gentle soul,” Jordan said. “Jamal was someone who wanted nothing but the best for the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.”

Ironically, Khashoggi, an outspoken critic of the government, supported many reforms Prince Mohammed bin Salman has implemented in the last two years. These reforms include lifting the ban on women driving and diversifying the economy, moves Western leaders applauded the crown prince for, according to the BBC.

“But in those days, those reforms were not so popular,” Jordan said.

Khashoggi was fired from Al Watan for publishing a column criticizing Islamic scholar Ibn Taymiyyah, considered the founding father of Wahhabism, the ultra-conservative, Saudi Arabian-state-sponsored branch of Sunni Islam.

What followed resembled a bizarre game of musical chairs, Jordan said. After being fired from Al Watan, then-Prince Turki bin Faisal Al Saud hired Khashoggi to be his public relations spokesman at the Saudi Embassy in London. Then, Turki bin Faisal became the Ambassador to the U.S., replacing Bandar bin Sultan Al Saud, and brought Khashoggi along with him to Washington, D.C.

Khashoggi lived in Washington, D.C., for several years. He fathered four children and became a permanent U.S. resident before returning to his position as editor at Al Watan in 2007, Jordan said.

Khashoggi left the publication again three years later after running an article criticizing basic principles of Salafism, the broader conservative Islamic movement of which Wahhabism is a part. For the next few years, Khashoggi wrote columns for several Saudi publications before being exiled from the country in 2016 for criticizing President Donald Trump, according to The Independent.

In September 2017, Saudi officials grew increasingly concerned with Khashoggi’s outspoken criticisms of the Saudi government, according to The New York Times. That same month, as he began writing columns for The Washington Post, top Saudi aides discussed ways to lure Khashoggi back into the country.

During this time, Prince Mohammed bin Salman said he would go after Khashoggi with “a bullet” in a recorded conversation later obtained by western intelligence agencies in an effort to find who was responsible for the journalist’s death.

THE FALLOUT

Over a year later, when he walked into the consulate, Khashoggi was met by a hit squad of about 15 Saudi agents who proceeded to kill him and dismember his body with a bone saw, Jordan said. Trump has been hesitant to blame Prince Mohammed bin Salman, Jordan said.

This sends a difficult message to journalists in the U.S., he said. “Generally, unless you’re with Fox News, you’re basically in [Trump’s] crosshairs,” Jordan said. “When you combine that with, apparently, a tolerance for the anodyne, unbelievable explanations coming out of the Saudis, I think it does send a difficult message for journalists here.”

Bob Little, a government professor, asked Jordan whether Saudi Arabia was stable and whether it is susceptible to an internal coup. Jordan said authoritarian regimes are inherently unstable, but that Saudi Arabia has kept most of its population from rebelling. He said the real risk of instability will come with the death of King Salman and the subsequent takeover by his son Prince Mohammed bin Salman.

In the fallout of Khashoggi’s death, Saudi Arabia named Princess Reema bint Bandar its new ambassador to the U.S.

Jordan said he thinks there is a chance that she will at least listen to the U.S. The question, he said, is whether or not she will be simply a figurehead who cleanses the stain the killing of Khashoggi created on the relationship.