By Matthew Brown

Layout/Web Editor

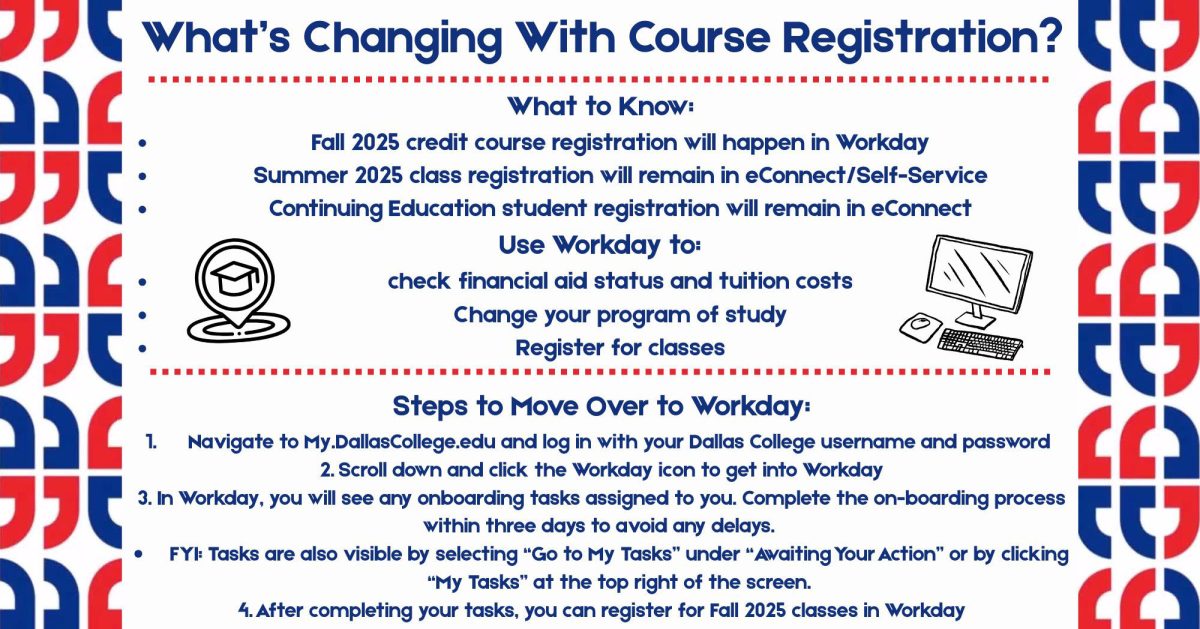

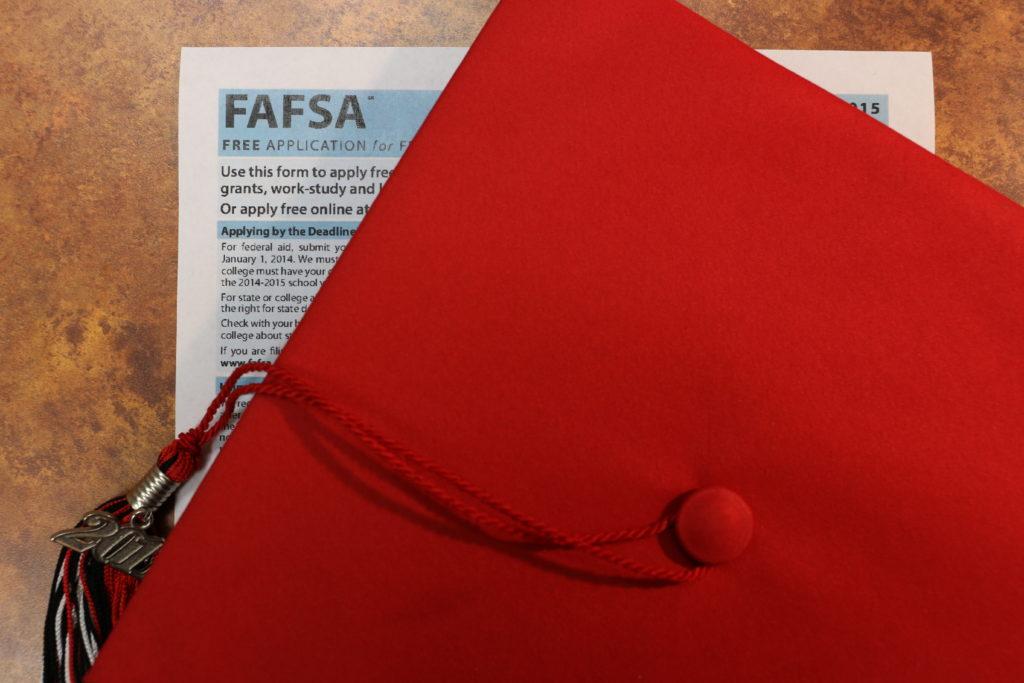

The state of Texas has taken an important step forward in helping more lower income students attend college. House Bill 3, the state education finance and reform law signed by Gov. Greg Abbott in June, includes a mandate that will require every graduating high school senior to complete the FAFSA, or Free Application for Federal Student Aid, to receive their high school diploma. This will go into effect in the 2020-2021 school year.

Seniors can opt out if they are over 18 or if a parent signs a form, and any students who apply for financial aid still do not enroll in college. Still, the new mandate could make tens of thousands more Texan high school graduates complete the FAFSA each year. That would help them find out about financial aid that could put going to college within their reach.

But many high school counselors and some college financial aid offices are already stretched thin, so carrying out the mandate may prove more difficult than lawmakers anticipated.

Filling out the FAFSA is one of the biggest parts of the college financial aid application process. Students are not eligible for federal loans or grants without submitting it, and many other financial aid providers – such as states, counties and universities – also use the information a student provides on the FAFSA to determine if they are eligible for more aid.

But Texas ranks 31st in the nation for FAFSA completion – only 55% of the high school seniors who graduated in Texas this year turned in a FAFSA, according to the National College Access Network, a national nonprofit organization that aims to increase access to college.

Louisiana is the only state where a policy such as Texas’ new FAFSA mandate has gone into effect. In the 2016-2017 school year, the year before Louisiana’s policy went into effect, only 44% of the state’s high school seniors turned in a FAFSA, according to NCAN. The next year, that number leaped to 77%. Texas’ mandate may not cause so big a spike in FAFSA completion, but even if its effect is only 25% as strong as Louisiana’s, it will mean over 12,000 more Texan seniors complete the FAFSA in 2020-2021 than completed it in 2018-2019.

John Wells, director of financial aid at Brookhaven College, said he has mixed feelings about the mandate. “No. 1, I see it as a good thing in that more students will be applying because they have no choice,” he said.

“The very act of just applying isn’t going to guarantee that they’re going to come to college,” he said. “But I think that it will give more of them the opportunity because it will show them that they’re eligible.”

Nikita Fisher, counselor at Early College High School, said: “I think this measure is really important, because I think that it’s going to open doors for a lot of students. But if we only focus on just the financial aid, and we don’t focus on the actual college application process, we’re still missing more than half the piece. Because you can have all the financial aid in the world and not go to college.”

The FAFSA completion rate at EHCS is already high. Its FAFSA completion rate last school year was 76% and peaked the year before that at 88%, according to the Dallas County Promise’s website. This is much higher than Carrollton-Farmers Branch Independent School District’s overall completion rate, which is 58% so far this year.

Fisher said one of the biggest driving factors in increasing FAFSA completion rates and college enrollment both at ECHS and in CFBISD as a whole over the last few years has been the Dallas County Promise, a new scholarship program. The program is open to students at 57 approved Dallas County high schools, is applicable at nine four-year universities and all of DCCCD, and offers to pay for all tuition not covered by federal or state grants.

A PERSONAL TOUCH

Aside from that, Fischer said the strategies that helped ECHS achieve such a high rate will be difficult to deploy across the rest of her district, let alone the entire state.

“I can say that I know all my graduating seniors – I know them by name, I know their families, because I’ve worked with them for all four years,” Fischer said. But EHCS accepts only 75 to 100 students per year, according to its website. A typical high school might have 400 to 600 students per graduating class, she said. And each student might not be assigned the same counselor all four years of high school, preventing them from developing the same level of trust.

“Without that personal touch, it makes it harder to mandate for students to come. For them, it’s going to be a much more difficult task … [because] if you are a first-generation college student and you’ve never done the FAFSA before, it can be pretty intimidating turning over all your financial information to the government. You don’t really understand why.”

Exacerbating the problem is the fact that guiding students through the financial aid application process is not school counselors’ only responsibility. “They’re also responsible for their social and emotional needs. They’re responsible for high school graduation, they’re responsible for credits,” Fisher said. “This is just one more thing for them.”

EXTRA HURDLES FOR NON-CITIZENS

The prospect of turning over financial information to the government can be even more daunting for students who are legal Texas residents but not U.S. citizens. They are not eligible for federal aid and cannot submit FAFSA application, but they are still eligible for state, county and university aid and can submit the Texas Application for State Financial Aid, or TASFA, which is similar to the FAFSA.

Wells said many students are afraid to complete a TASFA due to the current political climate. He said they worry that they are identifying themselves or their parents as undocumented. “Even though there’s not a central repository of that information, I can see where that fear exists.” Unlike the FAFSA, students cannot fill out the TASFA online. Instead, Wells said, a staffer at the college financial aid office has to manually enter the information on the forms into the financial aid department’s computer system. “So that’s very labor-intensive,” he said.

High schools also do not always provide students with all the documents they need to submit the TASFA, so the college takes on responsibility of making sure each student gets them. “Again, it’s just more work,” Wells said. “I can envision where now that all students are required to do that, that number is going to skyrocket.”

Early outreach

On top of making better connections with students, Fisher said she credits the success ECHS has had getting students to apply for financial aid – despite how intimidating or complex the process can be – to educating students and parents about the process early on in high school.

“We’re able to get such high rates because we tell parents from the time they come, ‘Hey, if your goal, and your dream, and your student’s dream is to go to a four-year university, we can support you in that, but these are the steps you have to do to get there.’ And because we taught them so often, there isn’t that fear of releasing your personal information to an unknown source, discussing your private financial situation.”

Fisher said ECHS starts talking to students about the FAFSA in their sophomore year. By the students’ junior year, the school is sending flyers home to parents explaining what the FAFSA is and what kind of information they will have to provide to complete it. ECHS also hosts a parent meeting that explains the basics of completing the aid application process.

Finally, in the students’ senior year, regional colleges begin sending representatives to hold college application and FAFSA completion workshops where they can help students directly, Fisher said.

LIMITED MANPOWER

Brookhaven is one of the regional colleges that reaches out to local high schools, including ECHS, to help. “We do high school nights – we do FAFSA nights when we’re invited. But some of them we do have to turn down. Just because, again, I don’t have the manpower,” Wells said.

“[Brookhaven] has one of the smallest staffs of financial aid in the district. So I certainly do not have the manpower to be able to constantly be sending people out,” he said.

“I would very much like to have a person or two just dedicated to outreach. But unfortunately, that is not the reality,” Wells said. “Since they are the ones that are requiring this, I’d like to see [the state] kick in some dollars and funnel that out to the school districts so [the district] could hire their own people,” he said.

Still, “a lot of it is going to have to be motivation on the students’ part,” he said.

“I think that the intentions were good. I don’t know, though, that the actual rollout of it was thoroughly thought through,” Fisher said.

“If we are as a state wanting to promote a college-going culture, you have to start somewhere,” she said. “And this is a really great first step. It just needs to be recognized as that. … If there’s no money, it’s hard to imagine yourself going.”