By Jacob Vaughn

Editor-in-Chief/Music Editor

To some up-and-coming bands, photos of their shows seem priceless. Their relationship with concert photographers, who offer free press, promotional material and a glimpse into the magic on stage, is a symbiotic one.

However, when these acts reach a certain level of stardom, they become more interested in curating their image than in capturing moments. This is why concert photography is dying.

“It’s something that has slowly been happening for decades,” Jason Janik, concert photographer, said. He equates it to death by a thousand mosquito bites.

Pop star Ariana Grande served one such low blow to photographers and media organizations in 2019 by hitting them with a new concert tour agreement. The contract requires photographers to hand over full copyrights to their photos from Grande’s shows, according to petapixel.com, a site covering camera and photography news.

Many other artists force concert photographers to abide by the three-song rule, which only allows them to take photos during the first three songs of a performance. Paul Natkin, a Chicago concert photographer, said the rule started during the ’80s with bands in New York, according to fstoppers.com, a site dedicated to educating up-and-coming photographers, videographers and creative professionals. Around the same time, music television began broadcasting into people’s homes. Artists wanted to look as perfect onstage as they did in their music videos.

The three-song rule shows up in Grande’s new contract, as well. According to petapixel.com, the National Press Photographers Association published a letter in response to the contract. The letter was co-signed by 15 other groups, including Alternative Press, LA Times and The New York Times.

“This surprising and very troubling over-reach by Ms. Grande runs counter to legal and industry standards and is anathema to core journalistic principles of the news organizations represented here,” NPPA General Counsel Mickey H. Osterreicher wrote in the letter. “While we understand your desire to maintain control over your client’s persona and intellectual property, we hope that you will appreciate our position.”

As a musician played several shows a week, I used to hope to God someone would come along and take photos of me performing. A shot of me doing my thing on stage would provide content for my social media pages and help get the word out about my music. However, if I had more control over the photos being taken of me, I could see wanting them to be shot during the more exciting parts of my set.

The three-song rule makes some sense on its own, Janik said. At more aggressive shows that might need security or at performances involving pyrotechnics, the three-song rule can serve to protect photographers. But he said acts’ management also step in to approve or reject a photographer’s work. When that happens, the photographer becomes nothing more than a part of the band’s marketing machine.

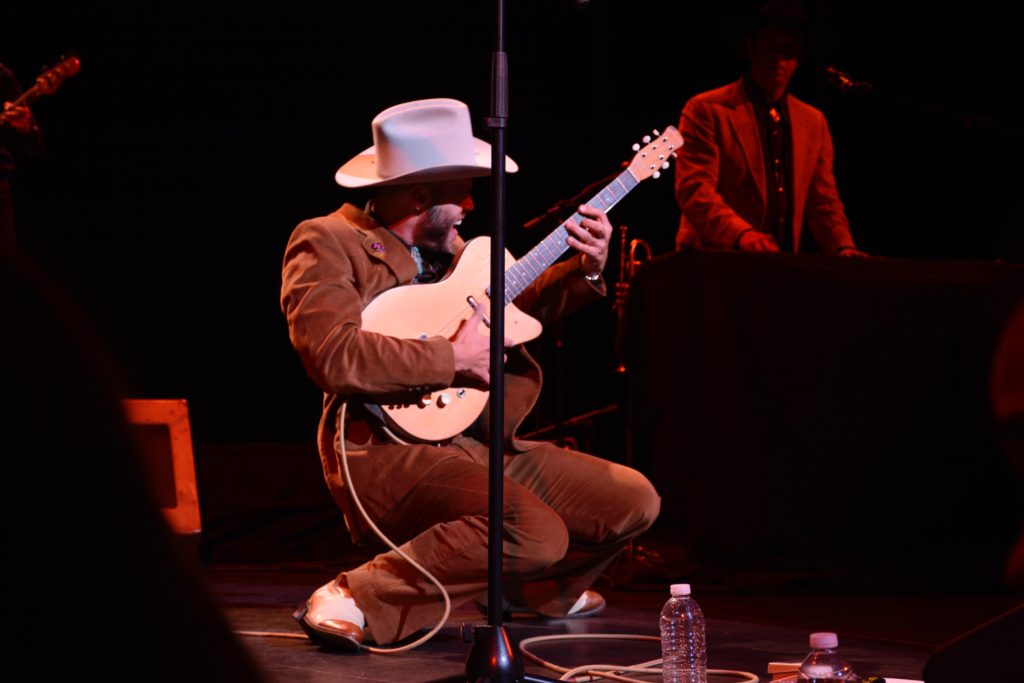

During a performance by Charley Crockett, a local blues artist, at the Majestic Theatre, rumors were floating around in the photo pit that the musician only wanted photos of his first and last four songs. As a beginning concert photographer, I had no idea what everyone was talking about. I thought – and still think – The photographer’s role is to document the full experience as objectively as possible.

Janik, too, said he sees himself as an archivist more than anything else. He said, “[I am] capturing and holding moments that those few hundred or few thousand got to experience.”

A photojournalist who signs contracts with bands is kind of selling his or her soul. The reality he or she is supposed to capture becomes manufactured, stripped of objectivity.

Mike Brooks, a contributor for the Dallas Observer, said, that generally, the bigger the band is, the more restrictive it is. When he shot a Marilyn Manson show, Brooks said, he was only allowed to shoot about 45 seconds of the set. Brooks said he understands where the bands are coming from, but that sometimes their restrictions are a little much. “Sometimes I do think they’re being divas,” he said. “It’s getting a little bit out of control.”

He said it’s hard to tell the difference between someone who wants to get a great photo and someone who just wants to be close to a celebrity. But he said there is another side to this – the big star-making machinery.

Tour photographers such as David Swanson, the only photographer allowed to shoot Jack White’s Dallas performance last April, help bands better craft the images they want to project to their fans. It seems to be a growing trend within the industry, Brooks said, and could mean the end of objective storytelling via photographs at concerts.

It will not be long before every photo we see is what bands and their managers mean for us to see. If there is a future for concert photography, it will be in shooting for smaller bands at DIY concerts. And if I’m playing at one of these concerts, you have my permission to take my photo.