By Erin Goldman

Opinion Editor

A flyer hung in a sea of colorful brochures and postings on the bulletin board outside my American Literature class. The flyer was for the Brookhaven College Counseling Center, offering free counseling to currently enrolled Brookhaven students. The bottom of the sheet had a single slip of paper with the counseling center’s phone number, the rest had been torn off. This sight struck a particular cord in me.

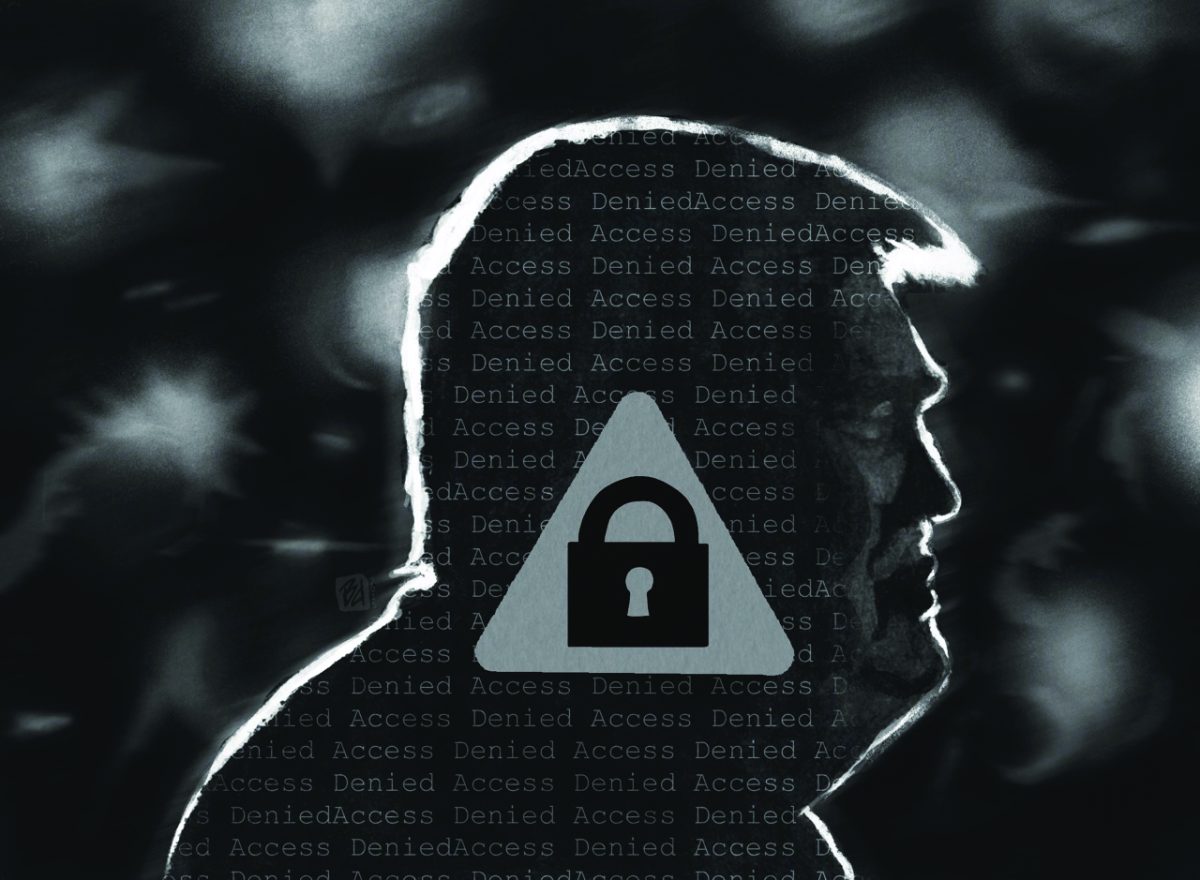

According to the National Alliance on Mental Illness, one in four Americans experience some form of mental disorder every year, and yet, mental illness is still stigmatized. I know this because I am one of those statistics.

Like many teens and young adults across the country, I spent years suffering in silence. According to NAMI, one-half of all chronic mental illness begins by the age of 14; three quarters

by age 24.

For those who know I have mental health issues, I’ve been viewed as weak, fragile and have been told people feel the need to walk on eggshells around me in fear that I will become the next Amanda Bynes. Not to mention the mass media’s depictions of mental illness often cultivates and reinforces peoples’ worst fears.

“A lot of times, people won’t seek help for mental illness because of the stigma,” Dr. Garianne Gunter, an adult and child psychiatrist with the South Carolina Department of Mental Health, said. “They won’t get help, until they’re near suicide or they are suffering from very severe symptoms.”

The Family and Medical Leave Act of 1993 is a US federal law requiring covered employers to provide employees job-protected and unpaid leave for qualified medical and family reasons.

“I have a patient who, after receiving mental health treatment, through FMLA, got her job back,” Jennifer Perla, a Dallas-based Licensed Professional Counselor-Supervisor said, “However, her employer no longer allowed her to do the parts of her job that she liked and she was forced to do more menial work instead because they feared she was too fragile and could not handle the stress.”

She was no longer considered a viable employee, simply because she asked for help.

According to the CDC, even though 80 to 90 percent of mental disorders can be treated with medication and other therapies, among the millions of affected Americans, fewer than half get help.

After the tragedy at Sandy Hook Elementary School, the issue of mental illness was brought to the forefront of conversations across the nation. “It’s always dangerous whenever something happens where a person who’s mentally ill might be involved,” Dr. William Sledge, medical director of the Yale Psychiatric Hospital, said. Sledge also said the evidence suggests that the mentally ill as a group are no more violent than the general population.

The danger is that associating mental illness with the atrocities of Sandy Hook perpetuates the notion that the mentally ill are inherently violent, and thus brings additional stigma to those suffering from a disorder.

State Senate Majority Leader Martin Looney, D-New Haven said: “In general, there has been a linking in the public mind between some of these mass shootings and mental health. I think that we have to recognize that the two are very much distinct.”

We need to educate the public about mental illness and teach the reality to those whose only exposure to mental health disorders is their television set and the ravings of movie stars who denounce the use of psychiatric drugs based on the writings of a dead science fiction writer.

One is no weaker for seeing a doctor for an anxiety disorder then going to see a doctor about asthma.

Seeing the amount of slips taken by students gives me hope. If we can’t advocate for ourselves, how can we expect others to advocate for us? It’s time to speak up and expunge the stigma.