The Courier staff responds to the attack on Charlie Hebdo

On Jan. 7, two armed men, brothers, entered the offices of satirical French magazine Charlie Hebdo. In all, 12 people died, including two police officers and several of France’s most celebrated satirists. This tragedy was a response to cartoons depicting the Prophet Muhammad, published by Charlie Hebdo staff.

It is not the aim of this paper or its staff to spark a discussion on people’s inherent right to practice or not practice the religions of their choice.

The subjects of freedom of press and expression, while fundamental to this discussion, will also not be covered at length.

Instead, we see this attack as an illustration of the side effects of globalization. With the click of a button, citizens of any nation, race or creed can interact, for better or for worse.

There is no question as to the necessity of Charlie Hebdo, or at least the necessity of the freedoms that allowed the magazine to criticize and challenge any force of power in this world.

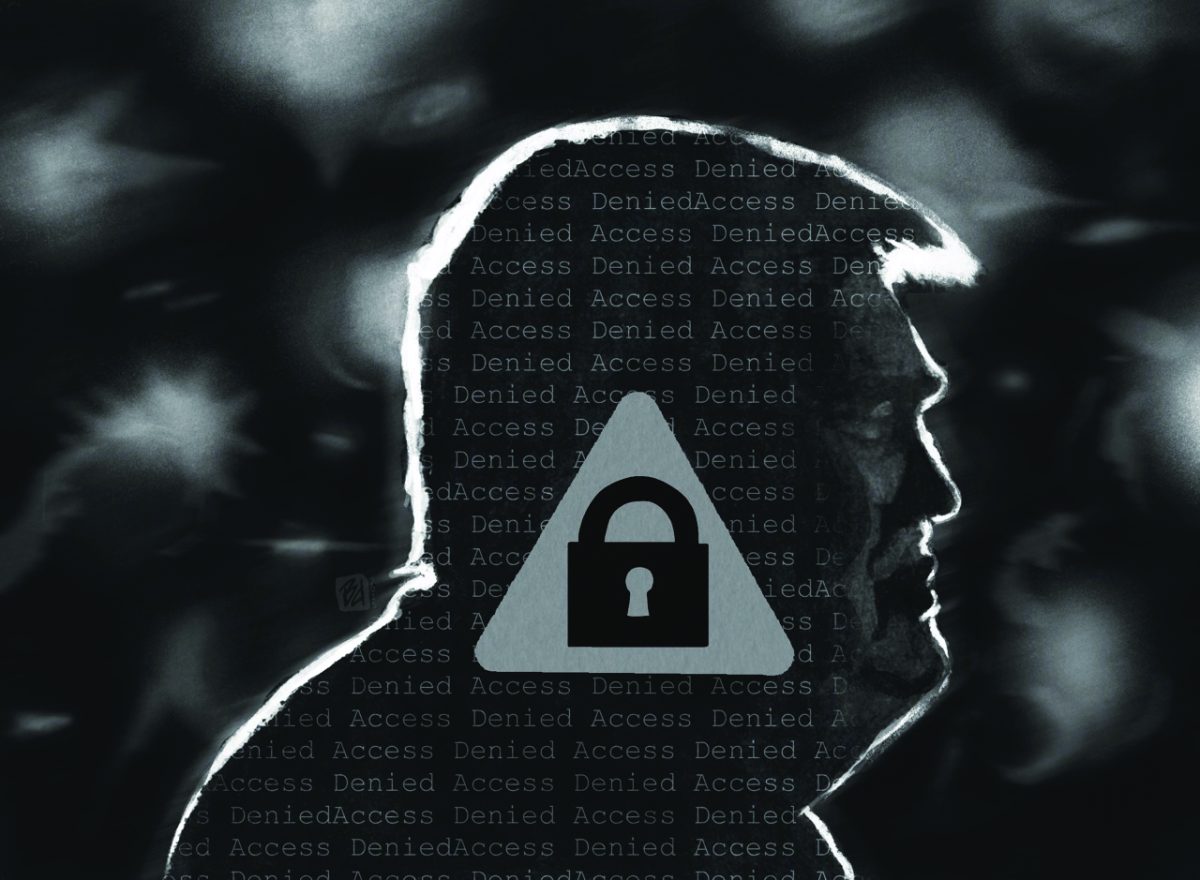

Yet these freedoms are repressed and punished in many parts of the world, parts that once were isolated but in the last few decades have become connected to the rest of the world through the Internet.

In 2011, Twitter and Facebook spurred on revolts across the Middle East. Cries of revolution filled our Twitter feeds. Videos of protesters fighting against injustice emboldened others to speak out as well.

People all over the world watched these revolts play out in real time as protesters recorded their experiences on smartphones. The western world was unable to ignore their struggle.

The information super highway has far more than one lane, however.

In 2012, a man in California of Egyptian heritage, Nakoula Basseley Nakoulaa, made a video and posted it on YouTube. The video, titled “Innocence of Muslims,” depicted the Prophet Muhammad as a fraud and a pedophile.

Violence erupted in the Middle East, leading to the deaths of four Americans, including U.S. Ambassador to Libya, Chris Stevens.

While the power of the Internet is capable of bringing us together, it is equally able to tear us apart.

As people took to Twitter to voice their outrage at the Charlie Hebdo attacks, a line in the sand was drawn. A line that demanded people declare their allegiance to justice and freedom with a hashtag, or out themselves as enemies with their silence.

Yet as the dust settled in the newsroom of Charlie Hebdo, the survivors went back to work, expressing their right to characterize.

Drawings and retweets cannot undo the loss of life.

While some may object to the subject matter depicted in the pages of Charlie Hebdo or in “Innocence of Muslims,” drawing cartoons, publishing YouTube videos and expressing thoughts and opinions are not things that carry a death sentence. These are not things that justify murder.

However, as the four corners of the world converge online, it becomes clear that all free countries must be ready to defend their basic rights, no matter what the cost.