By Joie’ Thornton

Senior Staff Writer

In honor of Black History Month

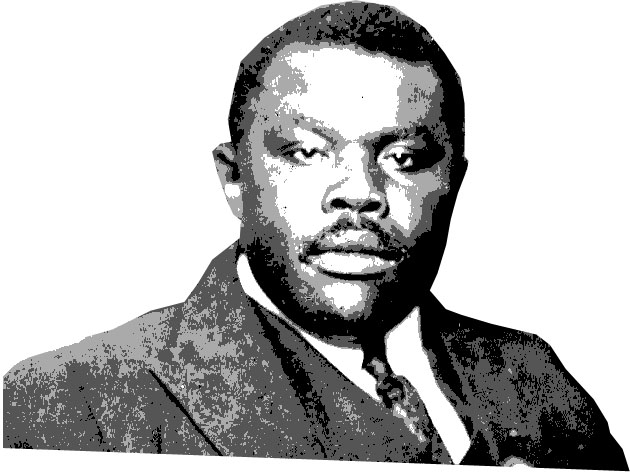

John Henrik Clarke (1915-1998)

John Henrik Clarke is known for his lifelonmg devotion to studying and documenting the history and contributions of black people in Africa. Clarke was the author of multiple articles that appeared in leading scholarly journals.

He also served as the author, editor or contributor for 24 books. With the help of the African Studies Association, Clarke founded the African Heritage Studies Association in 1968. He was appointed in 1969 as the chairman of the Black and Puerto Rican Studies Department at Hunter College in New York. In 1986, the African Library at Cornell University was named in his honor. Clarke played an important role in the early history of the African Studies and Research Center at Cornell University.

Ida B. Wells (1862-1931)

Ida B. Wells started her journalism career in Tennessee after she faced racism on a train ride from Memphis to Nashville in May 1884. That incident led Wells to pick up a pen and start writing about issues of race and politics in the South.

Many of her articles were published in black newspapers and periodicals. Lynchings in 1892 prompted Wells to write articles protesting the lynching of her friends and others. One of her editorials caused a mob to storm the office of her Memphis newspaper, Free Speech and Headlight, destroying everything.

Luckily, Wells was in New York at the time. She was warned that if she returned to the South, she would be killed. In the North, Wells continued to write about lynching in the U.S. for the New York Age, a black newspaper.

In 1898, Wells lobbied for her anti-lynching campaign in Washington. Until the day she died on March 25, 1931, Wells stayed committed to social and political activism.

Queen Nzinga (1583-1663)

In the 1500s, the Portuguese focused their slave-trading activities on the Congo and Southern Africa. In the 1600s, they encountered the bright and bold Queen Nzinga, who was determined never to accept the Portuguese conquest of her country.

She was an exceptional stateswoman and military strategist. Her meeting with the Portuguese governor is considered legendary in the history of Africa’s confrontations with Europe. Upon entering the meeting, Nzinga realized the only seat in the room was reserved for the governor. She promptly summoned a servant, who fell on hands and knees to become Nzinga’s “seat.” The governor never gained the advantage at the meeting, which resulted in an equal treaty. However, the governor could not uphold the treaty because of his thirst for slaves.

To solve the issue, Nzinga formed an alliance with the Jaga tribal chief. She conquered the kingdom of Matamba for her people and soon formed an alliance with the Dutch to resist the Portuguese. She became well known for the guerilla tactics she employed against the technologically superior Portuguese army. She led her warriors herself, despite being more than 60 years old. Never surrendering, she died on Dec. 17, 1663.

Marcus Garvey (1887-1940)

Marcus Garvey, a Jamaican-born black nationalist, created a “Back to Africa” movement in the U.S. In 1914, Garvey founded the Universal Negro Improvement Association in Jamaica. In 1916, he moved to Harlem, New York, and the UNIA thrived. Garvey became a public speaker and gave speeches across America. He urged African-Americans to be proud of their race and return to Africa, the homeland of their ancestors. He attracted thousands of supporters.

In 1919, to ease the return to Africa, Garvey founded both the Black Star Line, to provide transportation to Africa, and the Negro Factories Corporation, to encourage black economic independence. Garvey failed in his attempt to persuade the Liberian government in West Africa to grant land on which black people from America could settle.

In 1922, Garvey faced prison time in connection with mail fraud, and the Black Star Line went out of business. After prison, Garvey was deported back to Jamaica, and in 1935 he moved to London, where he died in 1940. In 1964, his body was returned to Jamaica, where he was declared the country’s first national hero.