Letter to the Editor

With two terrorist attacks in Paris in less than a year, a former Brookhaven College student recounts his experiences

The ticket in my hand read “Minsk, Belarus-Toulouse, France.” Upon arrival, I watched a French woman’s son play with a smiling girl. The children were happy, and a few passengers awaiting their luggage shared a moment of admiration.

Police patrolled the airport, fully clad in bulletproof gear and carrying high-caliber FAMAS assault rifles.

France was on high alert after the Charlie Hebdo shootings just over 10 months before the Nov. 13 attacks on Paris that took 130 lives.

A chic subway train took me to the metro stop, Esquirol. There were people of many nationalities on the train. Some seemed stoic, so I practiced a few French phrases on them to brighten their day.

Toulouse is called “The Pink City.” Its historic buildings weigh down like sagging pants due to poor construction. Scooters buzzed by shops that sell cheap hats and sunglasses at inflated prices. Young business professionals stood by trendy bars, sipping beer out of glass goblets. I noticed a copy of Charlie Hebdo laying faceup on the bar.

After several drinks, I grabbed a kebab from a Turkish-owned shop. That led me to meet Jacques Barbieri.

Barbieri invited me over for wine and conversation after I told him it was my first trip to France. I painted his portrait, and we talked about France’s influx of immigrants. He made a point to mention that France was unrecognizable from how he remembered it as a child.

Once a year, Jack visits Paris. He takes his bicycle and has a coffee at his favorite café. He commented on the mass shooting by saying: “Like the French population, I’m in shock. These attacks [are barbaric].”

My next stop was Bordeaux. For a week I sketched, painted and slept on rooftops. Once, I meandered into a hostel where I spent the night on the floor. A French legionnaire, something of a swashbuckler, taught me the phrase, “J’aime Bordeaux,” meaning “I love Bordeaux.”

He bragged about more than 30 kills in service. He took my sketchbook and pencil and drew me with an upturned nose after I sketched him. Our encounter reminded me of the true cost of freedom.

Bordeaux felt safe, even with the absence of police patrolling. One was free to wander about unmolested before the Charlie Hebdo attack.

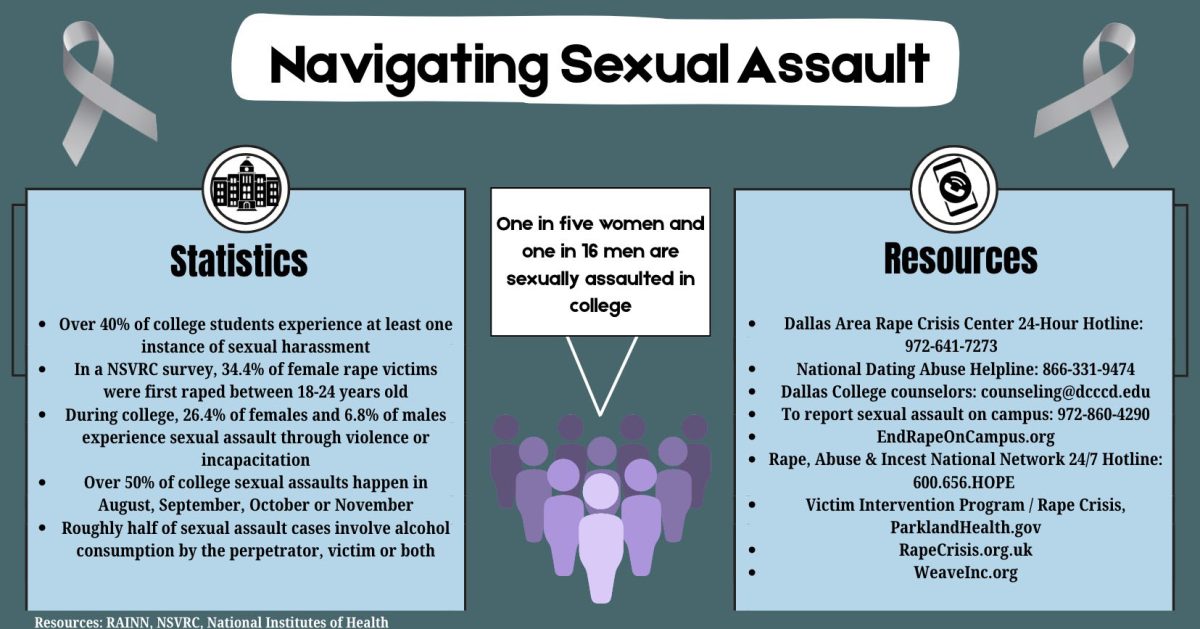

A major cathedral square in Bordeaux is a street market by day where immigrants sell everything from lightly used clothes to Halaal kebabs. I made many Muslim friends and they talked about the difficulty of being Muslim in France and that people’s self perception becomes skewed. “The Parisian tragedy saddens me,” Malik, who I met at the patio of a restaurant, said. “I was sad for the victims and the relatives of the victims, but I was also sad as a believer, for believers.” He described his love for his ancestral land, Algeria. He, however, was born in France. His father, a businessman, led his family to a better life in France. He said that, because he was disrespected for being the son of immigrants, he does not feel French.

Malik said it hurt him deeply to hear people speak badly of Islam because it is such an important part of who he is as a person. “I’m tired of that French media and political movement demonization of Islam. To associate Islam and terrorism has serious consequences in the Muslim population,” he said. “Islam preaches peace.”

I boarded a train to Nantes, a city known for its castles. My roommates prayed to Allah and I sketched them in prayer. There were days when I heard more Arabic than French.

I met Americans at a hostel, and spent a couple of days with them on a farm feeding goats and enjoying meals prepared by young New York chefs. They were traveling through the organization World Wide Opportunities on Organic Farms, which puts people in contact with small farms that offer a bed and food in return for work.

We slept under a roof on a cement foundation – they stayed in tents, and I got a hammock.

I went east to the city of Angers, where I again overspent and traded sketches for coffee. I slept in a large water pipe by the Château d’Angers, which was once the home of royalty. It began to rain. The rain collected at the bottom of the pipe and I put my box easel under me to make a bridge. I was shivering, drunk and lost, but I was happy.

I was referred to a free place to sleep by some people outside, which brought me to a refugee camp. Finally, I spoke Russian with someone. It had been several weeks since I heard the Russian language.

Chechens, Georgians, Azerbaijanis and others were there, behind a metal gate by metal shacks where men were separated from women and children by a tall wire fence. I felt as though I had struck a new low, so I drew and watercolored. The people I talked to were there to start a new life, to get away from tight political regimes and oppression.

I logged into my couch surfing account and continued my search for a place to crash. For the 30 or so people I wrote, the one positive reply came from Christophe Blanchot, near Valence by the Rhone Alps. I told him I didn’t have the money to make it to him from Angers, but he covered the cost of the ride, and my poor living standards became top class. We had coffee and toast with marmalade, and Christophe made lunch and dinner at his home overlooking the mountains. We drank traditional liquor from Marseille called Pastis and went hiking at the peak of Les Trois Becs.

Christophe said the only problem the French people really have with immigration is fear. “A lot of refugees and immigrants come from Muslim countries, and ISIS and other extremist Muslims make everybody afraid of Islam,” he said. “I think tolerance, generosity and benevolence are the only ways to solve the problem. But these behaviors are less visible than violence and hatred.”

Like many of the French people I met, Christophe was in disbelief over the violence and hatred taking place in his country. He was unsure if he should fear for his life and didn’t know what he could do to help. “But,” he said, “French people want to show they are strong. They don’t want to let the hatred win. They want to keep their freedom.”

– Vadim Dozmorov