By Jubenal Aguilar

Managing Editor

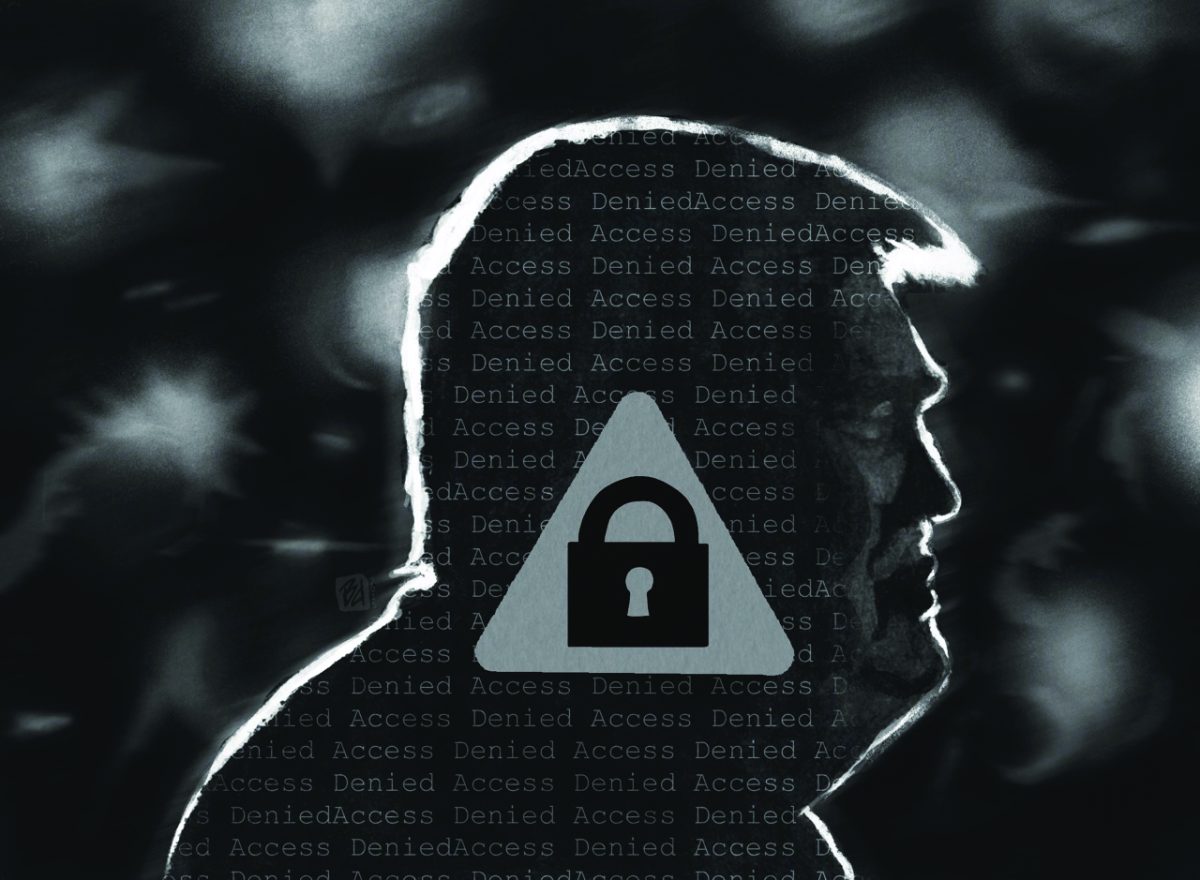

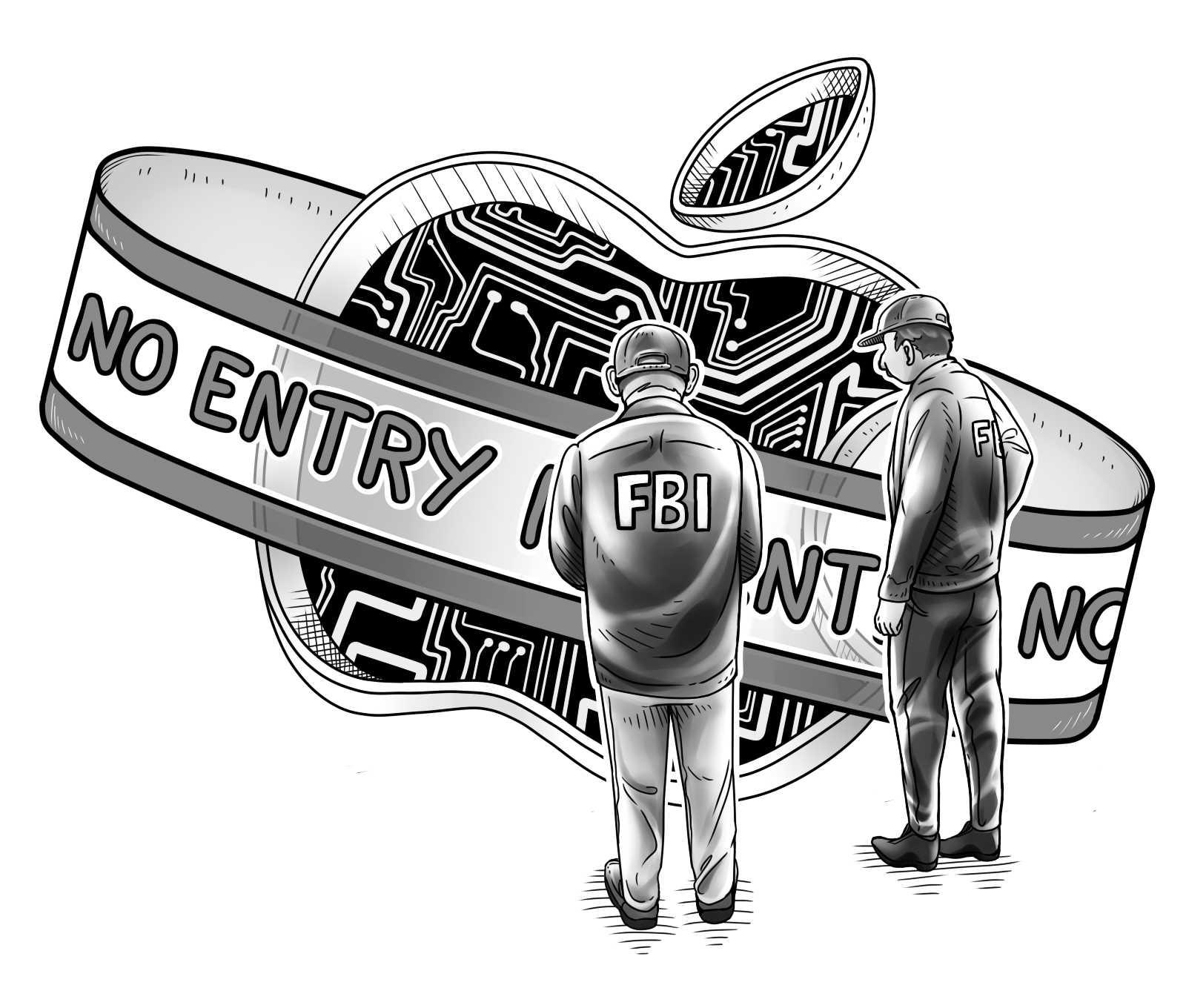

A single iPhone sparked a legal battle between Apple and the FBI over privacy and national security issues. The FBI wanted access to an iPhone 5C belonging to Syed Farook, one of two shooters in the San Bernardino, Calif. attack that left 14 dead last December. The agency wanted to know if the shooters conspired with the Islamic State group in carrying out the attack.

But the issue wasn’t about accessing a single phone. The FBI’s crusade on Apple was about acquiring the necessary precedent to undermine the digital encryptions tech companies have worked so hard to develop.

Apple refused to comply with the FBI’s demands, citing privacy concerns of its millions of customers worldwide.

The suit was dropped after the FBI, with the aid of an unknown third party, managed to unlock the iPhone on March 28, according to CNET’s Shara Tibken.

Apple is now off the hook from a possible damaging court decision that could have affected the entire tech industry.

The phone in question was protected by a passcode stored only on the device which lacks Apple’s Touch ID sensor. The sensor allows users to unlock their phones using their fingerprints.

The iPhone was believed to have a security feature activated that would wipe the data from the device after 10 failed attempts to enter the passcode. Apple provided the FBI access to iCloud, however, it yielded no information from Farook’s phone.

President Barack Obama’s administration and Apple met for weeks after the shooting to discuss the case. “When the talks collapsed, a federal magistrate judge, at the Justice Department’s request, ordered Apple to bypass security functions on the phone,” according to The New York Times’ Eric Lichtblau and Katie Benner.

The FBI cited the All Writs Act of 1789 – a 227-year-old law – in an attempt to force Apple to comply.

“It’s a sweeping legal gesture that gives courts the authority to issue orders compelling people to do things, so long as it’s for a legal and necessary reason,” according to Limer’s report.

The FBI used an archaic law, designed to force individuals to obey court orders during early stages of independence in the U.S. It attempted to bring old rules, designed for old times, into a digital age – an age that warrants rules of its own.

To access the iPhone, the FBI demanded Apple build a new version of its operating system, circumventing certain security protocols built into the iOS device. This would allow the agency to attempt millions of passcode combinations without wiping the phone’s contents, according to The New York Times.

The custom iOS would have essentially created a back door for the FBI to access the phone.

In an open letter to its customers, Apple CEO Tim Cook said: “The implications of the government’s demands are chilling.”

The government could use this case as precedent to request access to other devices – forcing other tech companies to comply with similar demands. The scope of the demands, Cook said, would eventually increase.

Cook continued on to say: “The government could extend this breach of privacy and demand that Apple build surveillance software to intercept your messages, access your health records or financial data, track your location or even access your phone’s microphone or camera without your knowledge.”

Cook compared the creation of a back door for the iPhone 5C to having a master key. The FBI would have the power to access any iPhone, in any place, at any time.

If it were to fall into the wrong hands, any criminal organization, foreign government or hacker could use it to steal valuable information.

The FBI’s success may have ended the legal battle, but not the encryption war. It didn’t need to establish a precedent; it just needed to find a way around it.

And now it has.

Since unlocking the phone, the FBI has offered to help local law enforcement agencies unlock other devices when permitted by law, according to CNET’s Zack Whittaker.

However, the FBI revealed the technique only works on one model, according to CNET. None of the newer models can be unlocked by the government.

Privacy is not the only issue – national security is also at stake. Criminal activity can be protected inside locked, encrypted devices and lost if the criminal is not found or dies unable to provide a passcode.

According to Mike Levine, an ABC News digital journalist, in a Feb. 25 hearing, Rep. David Jolly of Florida, said: “I think Apple leadership risks having blood on their hands.” Jolly said the San Bernardino shooters gave up their privacy and civil liberties the day they committed the attack.

But it’s not Apple’s fault an iPhone was used by one of the shooters. Apple can’t be blamed for the attack in the same way gun companies are not blamed for the daily shootings and robberies across the country. It’s the FBI, and government, who failed to identify and prevent the attack in the first place.

Regulating digital encryption is not the answer. It’s an invasion of our right to privacy.