By Jubenal Aguilar

Editor-in-Chief

[email protected]

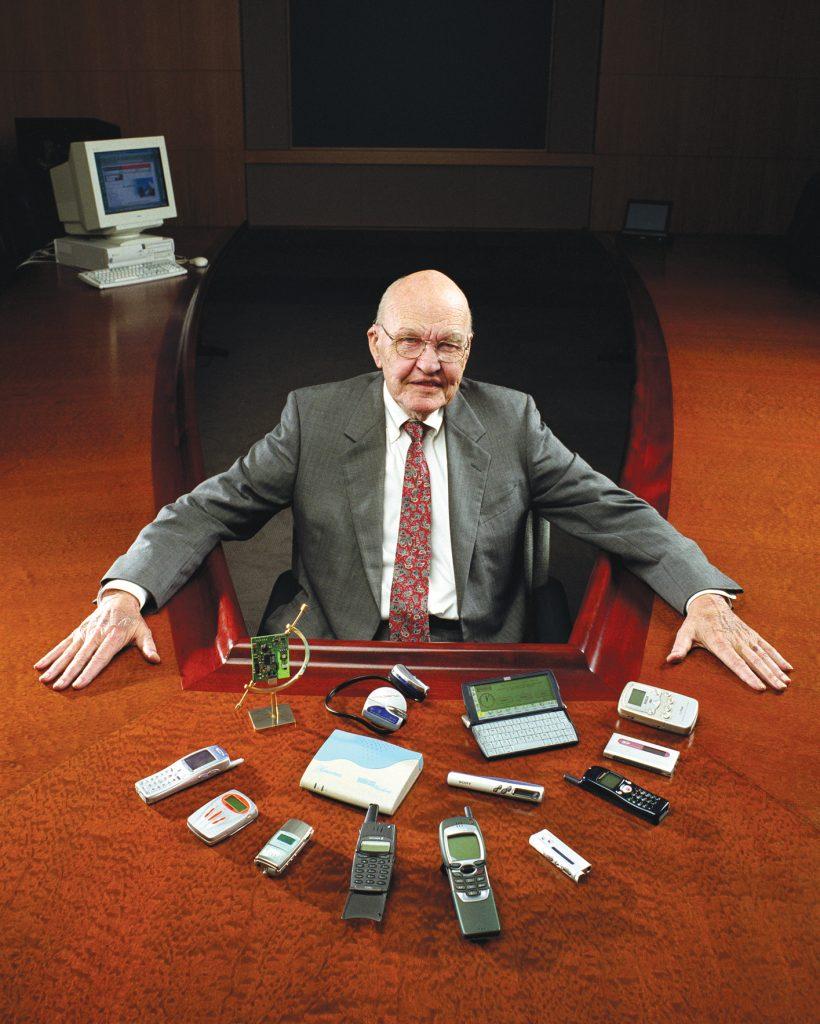

Nowadays the integrated circuit is everywhere and in everything – from electronics to household appliances to space technology. Its creation in 1958 by Jack Kilby revolutionized the electronics industry and led to a breakthrough that allowed for the accelerated development of smaller, more efficient electronic components.

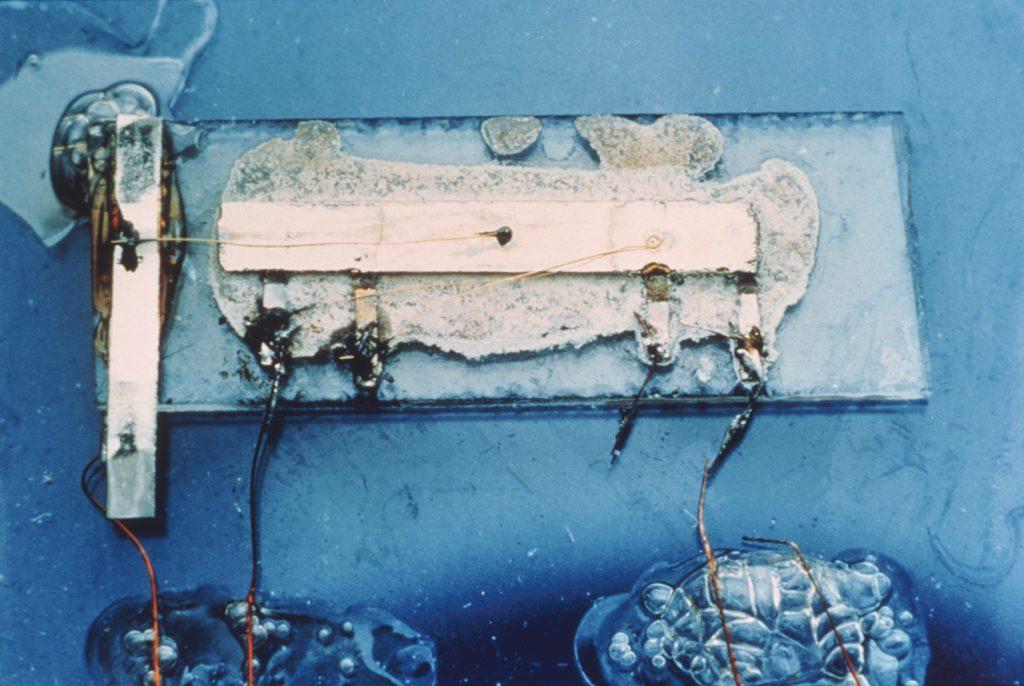

Created in Dallas’ Texas Instruments labs, the first integrated circuit was a simple device made of only a transistor and other components on a 7/16-by-1/16-inch slice of germanium, according to ti.com. Kilby’s breakthrough made the development of sophisticated high-speed computers and large-capacity semiconductor memories of today’s information age possible by solving a half-century problem that limited the advancement of electronics at the time.

Kilby was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics on Dec. 10, 2000 in Sweden for his achievement and its subsequent impact on the world, according to The Nobel Foundation.

In the 60 years since its invention, the integrated circuit, also known as a microchip, continues to be “the conceptual and technological foundation for the entire field of modern microelectronics,” according to ti.com.

“Chips are in everything from your car to your toaster and watch,” Charles Cadenhead, a Brookhaven College computer information technology professor, said. “Without them, social media would still be notes passed in class and search engines would be phone books. They are everywhere and soon will be in everything.”

Kilby joined TI in May 1958.

“My duties were not precisely defined, but it was understood that I would work in the general area of microminiaturization,” Kilby said. He realized that since the company made transistors, resistors and capacitors, a repackaging effort might provide an alternative to the Micro-Module.

The Micro-Module program was the U.S. Army Signal Corps’ attempt to solve the Tyranny of Numbers, according to allaboutcircuits.com. Micro-Modules were standardized sizes and shapes for electronic components that had the wiring built in. The wire components were built into the chip, allowing the modules to snap together to make various circuits.

To solve the problem, Kilby designed an intermediate-frequency, or amplifier, using components in a tubular format and built a prototype. “We also performed a detailed cost analysis, which was completed just a few days before the plant shut down for a mass vacation,” Kilby said. The cost analysis gave Kilby insight into the cost structure of semiconductor housings.

However, Kilby did not feel Mirco-Modules were the solution to the Tyranny of Numbers.

“In the early ’50s, people could begin to visualize electronic equipment,” Kilby said in an interview in the late 1990s. “It was much more complex than anything that had been realized. And if those equipments had been built with existing technology, they would have been too big, too heavy, too expensive and use too much power to be useful. So that was collectively described as the tyranny of numbers. The number of parts that were required were just prohibitive.”

As a new employee at TI, Kilby had no vacation time and was able to work on the results of the IF amplifier exercise.

In searching for an alternative, Kilby concluded that semiconductors were all that were required. He realized that passive devices – resistors and capacitors – could be made from the same material as active devices – transistors. “I also realized that, since all of the components could be made of a single material, they could also be made in situ interconnected to form a complete circuit,” Kilby wrote in a 1976 article titled “Invention of the IC.”

Kilby’s first unit was assembled and demonstrated to Willis Adcock, a physical chemist and TI electrical engineer, Aug. 28, 1958. “Although this test showed that circuits could be built with all semiconductor elements, it was not integrated,” Kilby said. “I immediately attempted to build an integrated structure as initially planned.”

Kilby completed and demonstrated the first integrated circuit on Sept. 12, 1958, which was publicly announced at a press conference in New York City on March 6, 1959, according to ti.com.

While Wikipedia, Britannica and biography.com, as well as other online sources, list Jefferson City, Missouri as Kilby’s birth place, he wrote in his own biographical entry for the Nobel Committee: “I was born in Great Bend, Kansas … I grew up among the industrious descendants of the western settlers of the American Great Plains.”

Kilby’s father owned a small electric company that had customers in rural western parts of Kansas. After an ice storm took out telephone and electric poles, his father coordinated with amateur radio operators to communicate with customers. “My dad’s goal was to do whatever it took to run his business and to help people, but I thought that amateur radio was a fascinating subject,” Kilby wrote. “It sparked my interest in electronics, and that’s when I decided that this field was something I wanted to pursue.”

Kilby earned his Bachelor of Science and Master of Science, both in electrical engineering, from the University of Illinois and University of Wisconsin, respectively.

Kilby said most of his classes at the University of Illinois were in electrical power, but also took vacuum tube engineering physics courses to satisfy his childhood interests.

“I graduated in 1947, just one year before Bell Labs announced the invention of the transistor,” Kilby wrote. “It meant that my vacuum tube classes were about to become obsolete, but it offered great opportunities to put my physics studies to good use.”

After completing his master’s at the University of Wisconsin, Kilby and his wife moved to Dallas where he joined TI in 1958. “TI was the only company that agreed to let me work on electronic component miniaturization more or less full time, and it turned out to be a great fit,” Kilby wrote.

During his career, Kilby pioneered military, industrial and commercial applications in microchip technology, according to ti.com.

“I headed teams that built the first military systems and the first computer incorporating integrated circuits,” Kilby wrote. “I also worked on teams that invented the handheld calculator and the thermal printer, which was used in portable data terminals.”

Kilby retired from TI in the 1980s, but continued to maintain a significant involvement with the company, as well as consulting on various industry and government projects.

He died June 20, 2005 of cancer.

Kilby held over 60 U.S. patents, according to pbs.org.

He was awarded the National Medal of Science in 1970 and inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame in 1982, according to TI’s website. “Seeing your name alongside the likes of Henry Ford, Thomas Edison and the Wright Brothers is a very humbling experience,” Kilby wrote.

He also received the Franklin Institute’s Stuart Ballantine Medal, the National Academy of Engineering’s Vladimir Zworykin Award, the American Society of Mechanical Engineers’ Holley Medal, the IEEE’s Medal of Honor, the Charles Stark Draper Prize administered by the NAE, the Cledo Brunetti Award, and the David Sarnoff Award, according to ti.com.